Opinion: Climbing And The Olympics An Indian Perspective

Varlakonda, a crag on the Bangalore-Hyderabad highway - once vulnerable rock, now secured by Government orders.

Let me begin with a hypothesis: I think we're overestimating the impact of the Olympics on climbing. When I heard about the final nod, I was confused at the elation about this 'long overdue' recognition. As if the perennial medical student finally became a doctor. It took some effort to re-examine the situation objectively and locally. Eventually, this article will reveal itself to be about two major things: Parenting and vulnerable rock.

In more developed climbing cultures, this has been written about as an elixir for funding and infrastructure, and a serious concern for fragile outdoor areas. In India, it breathes differently. To get a sense of why, a little background on history and social ethos helps.

India: The attitudes

I spoke to Keerthi Pais, Chairman of Youth Development at the IMF (Indian Mountaineering Foundation and advisor to GETHNAA (General Thimayya National Academy of Adventure), Department of Youth Empowerment and Sports, Govt. of Karnataka. For over two decades, Keerthi has been at the centre of the competitive climbing scene as a coach. And yet competitions are far from his personal approach to the sport.

Then why venture into this web? Because, when he started climbing in 1993, convincing talented youngsters to push hard for the 'sense of challenge' and 'personal victory' wasn't cutting it. For that matter, simply meeting performance-oriented climbers was hard. If athletes had to get serious, then parents needed to be sold. True in many parts of the world, but in India children typically have less bargaining privileges.

Parents decide what is worth pursuing based on tangible metrics—medals and ranking, public recognition, scholarships, financial rewards and job opportunities. Competitive climbing provides a more suitable eco-system for these values. Largely, this is a generation raised on survival mode to whom the idea of climbing, or any activity, as its own reward was unfathomable. India still lacks a respectable minimum wage system, and has massive wealth distribution gaps. The mentality is understandable. However, it has trickled up the class ladder; it's not just the preserve of the disenfranchised.

Almost every time people see me with a crashpad, I have to go through the usual maze of clarifications: It's not for the government, I don't guide foreigners and no one is paying me. Now, imagine Keerthi's battle in trying to nurture a promising young girl, back in the late '90s. When Archana Jadav's mother showed up at the government-built climbing wall in Bangalore, Keerthi had to answer a series of questions.

'What if she falls?' He explained how a belay system worked to convince her of Archana's safety. Then she asked 'What is the benefit of this?' 'I said she has tremendous potential to win a medal at the state level...I think that's what did the trick' Keerthi recalls. Archana was anxiously waiting in a corner. Keerthi's answers would determine whether she had a future in climbing or not. Desperate, she came up and said 'Pleeeassee mummy...'

'Permission to climb a 42-feet wall, that too for girl, was HUGE,' he says, alluding to the country's patriarchal overtones. Archana went on to become one of India's greatest, and continues to stay in the sport as a comp judge and outdoor products distributor. Using the attraction of competitions, Keerthi managed to get more young, performance-driven climbers into the sport. The 2000s saw a surge in this breed, across the country.

“Of the many sports parents can ‘put’ their kids into, climbing goes from an esoteric pursuit to an attractive option with new found ‘prestige’. No more explanations about belay systems, health benefits, creativity and problem solving, adventure and exploration. A simple ‘It’s an Olympic sport’ will do.”

Now, here we are with the Olympics looming. 'It makes a huge difference in the mentality of people getting their kids to climb. That's where my mind went first.' Of the many sports parents can 'put' their kids into, climbing goes from an esoteric pursuit to an attractive option with new found 'prestige'. No more explanations about belay systems, health benefits, creativity and problem solving, adventure and exploration. A simple ‘It's an Olympic sport’ will do.

Athletes aren't particularly gleeful about the format, but the idea of being an ‘Olympian’ holds allure. Bharath Pereira will be India’s entry at the 2018 Youth Olympics in Buenos Aires. The details of selection are vague, but he was picked based on his performances at Asian level competitions. I wanted to gauge what, in his eyes as a competitor, was the ultimate prize; Olympic Gold, World Championship or IFSC World Cup overall. 'Definitely Olympic gold. If one Indian wins, it would greatly benefit the sport’s recognition.’

Among other social aspects, this might hold relevance for schools with funds in their sporting programs too. Perhaps the evolved competitive pyramid of zonal, national, international and Olympic levels might make them consider a climbing wall?

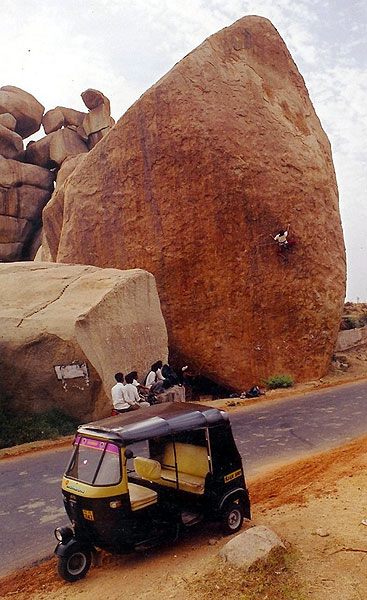

Reactions to 'climbing' in Hampi, circa 2000-01

Olympics and the outdoors

India has plenty of rock. PLENTY. And it's a valuable commodity. One evening, when I was at Avati, a crag near Bangalore, I remember a thunderous blast on a hill opposite to where we were climbing. Quarrying, mostly illegal. We were actually planning a session on that hill for the evening.

A common concern about an Olympic-induced climbing boom is the stress it will place on crags—overcrowding, pollution and more. In India, it's almost reverse. An endless supply of climbable rock that, due to lack of participation, is left vulnerable to litter and worse, quarrying. 'More people going to the rocks is a NEED. A necessity to protect our forests and natural areas,' Keerthi says, laughing, but in a tragic way.

Even in well developed areas such as Hampi, the fight against quarrying exists. Ask Pil Lockey, Hampi's primary developer, and he'll give you so many stories about it. A particularly heart-breaking one is of an entire area that his friend Squib had developed, which two seasons later was blasted. Not one boulder left. Many classics that still remain, in negotiated ‘no-blast areas’, have bleak names referring to this ongoing conflict: Destroy The Future, Don't Break, Visions of Doom. A simple way to save endangered rock is to climb, give nearby villages some business and cultivate the perception that rock is valuable if preserved. (Pil's written about it in detail on his blog, here)

In our medal-obsessed culture, will Olympic climbing necessarily translate to more people outdoors? Probably not. But, governments will recognize the sport. They will want more of an infrastructure built around it. If played right, this could include more areas 'officially' designated for climbing. A government order in this vein could offer reasonable immunity against quarrying. In a semi-lawful land, this is a bright spot.

It's foolish to think we're immune to overcrowding though. In wild Himalayan areas, for example, this could quickly become a concern.

What does India need?

From a performance standpoint, what India lacks are coaches, and then climbing gyms. We barely have one coach per state, let alone gym or city. Will the Olympics improve this situation? Hard to say.

Sport in India is a state subject. So, economic changes will be driven from that sphere. 'If private gyms are depending on a boost from the Olympics, that's not going to happen,' Keerthi says, having founded a bouldering gym, Equilibrium, himself. What we might see is an independent climbing federation and more affiliated bodies. More government sanctioned climbing walls and thus, outlets for hold distributors or makers. Hopefully, an eventual investment towards building coaches.

These coaches are then capable of shaping formative attitudes about climbing. Is it a sport whose utility is competing and winning? Or a lifelong friend that presents more challenges than imaginable?

These attitudes will form the foundation of climbing's future in India. This is a delicate business and will reflect in the way the nation's artistic culture itself evolves. For me, that's the key—to recognize that climbing moonlights between sport and art, while fully occupying both spheres. Ingraining that will ensure a more wholesome, sustainable growth for it. At best, the Olympics can be used as a timely ally.

My hypothesis stands, but on more shaky ground.

Bangalore based boulderer, radio person and writer