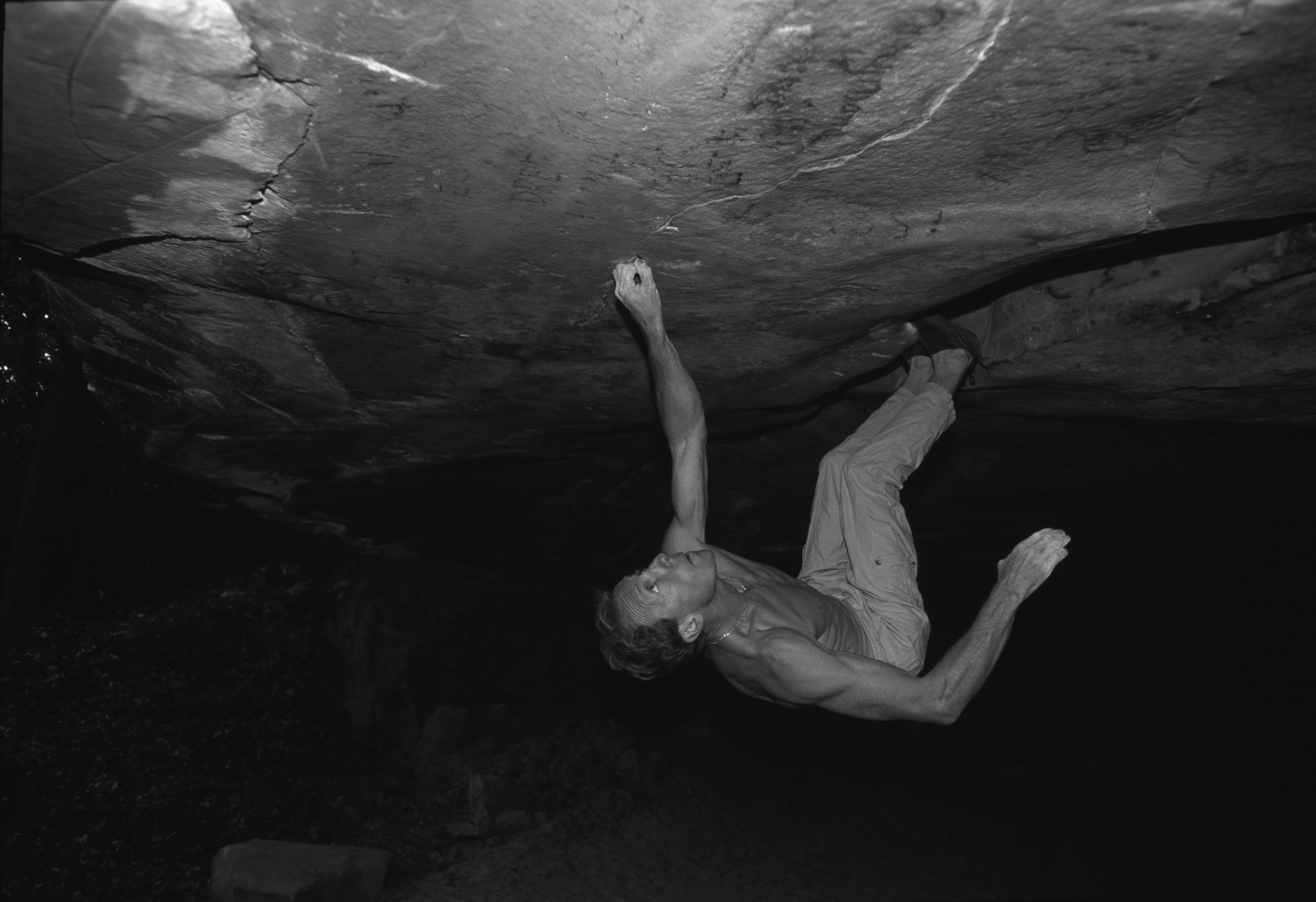

Jacky Godoffe Interview

La Bassine, Puiselet Font 7c (V9) Photo Aurore Godoffe

Like most superlatives, the word 'legend' is one frequently overused in today's world. However, if there is one climber alive today who is truly worthy of that title it is Jacky Godoffe. Hugely influential in his home area of Fontainebleau and way beyond, Jacky has pushed the boundaries of what's possible on the hallowed sandstone again and again. The quintessential Bleausard of the modern era with an untouchable legacy, Jacky is still active into his 60s. To many climbers he is quite simply Fontainebleau personified.

When you look back over your climbing career, which are the first ascents which really stand out to you as landmark achievements in your climbing?

I rather like to consider looking to tomorrow as a better option for me than looking backwards, but if I try, I would say in 1984 after the reading of the book from Reinhold Messner The 7th Grade I found the inspiration to introduce the 8th grade in Font. The boulder problem was C'était Demain and a few years later in 1986 I sent three kind of highballs in Cuvier Rempart: Big Boss, Fourmis Rouges and Tristesse in Cuvier, all three Font 7c (V9) without any pads. I felt at this moment that I was unstoppable with no fear. These boulders were for long the symbol of a new dimension for bouldering and a part of the famous "big five". The same year I sent the first Font 8b (V13) Fatman that was for me the best symbol of my huge ego to push the boundaries. Ten years later I was close to sending what has now become The Island 8c. I brushed it and tried it for more than a year, eventually I gave up with the line as it had became too much of an obsession. I think the problem Partenaire Particulier was also for me a fantastic achievement and an amazing line. I also remember Partage I sent together with Marc Lemenestrel during the same kind of search for a line that could be inspiring. Ten years ago I discovered an huge roof Le Roit d'Orsay with an incredible 360 move that was for me symbol of hybrid climbing style between rock and resin. All in all, I was first obsessed by grades, then by amazing lines of rocks, eventually by a search of new moves.

Many climbers go through the focus grades at some point. What do you think drove that obsession for you at the beginning?

What drove this obsession? Good question. Who knows exactly how things turn and why? I think I was at the time capable of pushing the limits and during a period I thought I was in charge of the playground somewhere. I was in the same time able to do very hard boulders quickly in specific styles that suited me perfectly. So I decided to give two hundred percent of my energy to this kind of search. Maybe the alchemy is between to doubt and to dare. A bit like a poker game. You never know exactly what will happen but it's very exciting. To be honest, at this time bouldering was not as popular as it is now and I thought I could maybe have an impact and create some changes. Basically I felt like an animal with a kind of instinct that I combined with my strength, especially my body tension and a special ability to speed up at the right moment. Sometimes I was able of doing a move using energy instead of just pure power, as in karate. During a period I had the feeling that I was able to walk on the air to fight against the gravity. It's a fantastic feeling to recycle the energy of a move and be attracted to the top instead of the ground. Nothing very rational—in fact it's more based on intuition and confidence.

Irreversible Maunoury 7c, photo Aurore Godoffe

Bouldering had nowhere near the popularity is does now when you put up some of those early classics. With a much smaller scene where did you find your inspiration? Was there anyone in the climbing world who pushed you to progress?

Reinold Messner was inspiring for me because he was inspired to do things his own way, developing a new grade in alpinism and climbing, and having a vision about the future, development of competition and training. I wanted to be unique even if it was presumptuous of course. My parents, especially my father, introduced me at a very young age to the power of people, whatever nationality, skin, sex and so on. Life sometimes offers opportunities, and I was very lucky to know early on in what could make me happy in the longterm. The climbing community was very small indeed, with strong and different characters. With bouldering not popular at all, I found the opportunity to discover what I was made for. But all in all it was an amazing experience to be at the right place in the right moment. I became a kind of icon of bouldering all over the world. It was exciting to learn how to survive with this popularity; I still share the same philosophy about the power to be instead of to have.

“Success in climbing is just the tip of the iceberg. The most important thing for me is how to deal with such an important passion and also the rest of life”

That's a great philosophy to live by. For many people it would be easy to get carried away with that success. How did you survive and cope with that popularity?

I'm a bit of an idealist. Maybe it's not that easy to have relationships with people that give you their respect just because of your ability to do something. For me people don't have to consider you because of what you do but because of why you do it. I learned that in the early days of my climbing career and I was very proud of the success. Then I noticed that it was most of the time a strange position be in and I changed my state of mind. Success in climbing is just the tip of the iceberg. The most important thing for me is how to deal with such an important passion and also the rest of life. I am lucky to have had 5 children, and none of them never ever climbed, so at home at least I'm just a human trying to surf on the waves of life. This is a way harder than the most difficult boulder I ever climbed.

Quoi de neuf 8b+ (V14) Orsay, photo Radek Kapek

Bouldering has obviously increased dramatically in popularity over the past decades. How do you feel about the way that has impacted the forest of Fontainebleau in particular?

Obviously it's hard now to find a quiet place whatever the moment—except maybe in August! I'm happy that so many people now appreciate the values of bouldering in such a beautiful and diverse place as Fontainebleau. I couldn't complain. First of all because I have a part of the responsibility for this development, also because it's not such a drama. Even in the most popular areas, the quality of the sandstone is amazing and it's still possible to climb without feeling like you're sliding on pieces of soap. Some areas seems to me now like a climbing gym; so many developments with the appearance of crash pads, training, internet, the video online and so on. I personally think climbers are respecting the forest more and more, most of the time taking care about what they do. Funny to think that 40 years ago, the famous Bas Cuvier was busy with 20 climbers in the same time in the place and now it's quiet with the same number. We are lucky here that forest is so big, about 2000 square kilometers, and people can go to many different areas so the impact is not only in one place

You've managed to continue your climbing career through all that time. How has your approach to the sport changed over the past decades? Do you still push yourself just as hard as you did?

I would say that my approach has been very different over the years.

In the beginning I was a performer especially in Font. It was for me inspiring, a mix between high performance and a dream to be in such a beautiful place. At the same time, soft about the touch and hard about moves. I had time, so I spent many hours walking through the forest searching for lines that could allow me to push the limits, mine and the limits of the sport. My obsession was 8a (V11), then 8b (V13), and eventually 8c (V15) (but I never did reach this third point). It was a way to learn that the process was eventually more interesting than the outcome. I don't mean that outcome is not important—it is—but the main change for me after some ten years of obsession for grades was a new angle of perspective. Starting for a blank piece of rock, playing with doubts strength and time, trying to put all together all the puzzle. And at the end most of the time, a feeling of being at ease. The most exciting moment was not the final one but the search. The next 20 years I was more focused on the magic and inspiring lines whatever the grade. I also had a time factor to deal with. I became father of 5 children and I had less time to spend in this secret garden. For the last 15 years I would say that honestly I was focused on sharing experience with others. I was lucky to become route setter so that I had the opportunity to explore this dimension and the others I've experimented with before under the spotlights.

Now I still love to climb in the forest as much as the first day I started to climb. Because of this place, because of the sandstone, because of its kind of magic. I still have projects because one thing has never changed for me: Tomorrow will be better than today, and I always need to be surprised by life. So what could be the next step? I'll let life decide if my body will continue to follow my crazy aspirations for climbing. I wouldn't complain, until now in my early 60s, I was lucky with genetics and didn't have any injuries or limitations. So I enjoy and I guess that will be like this for long. If not I'll be back to music or anything else. Who knows? Life is not a quiet river but I love it.

How has that approach you've developed to climbing impacted the way you think about your route-setting?

Three different elements came directly from my experience in rock climbing: Doubt, complexity and personal adaptation to a situation that can have several different answers (depending on the size and strengths). A rock climbing line never climbed is a question nobody has any answer to. The main difference indoors is the time allowed; in an open project outside everyone has all the time he wants. In competition the time is limited. I learned year after year how to introduce a bit of each element to make climbing more understandable to neophytes. I also tried to create a common language for a route-setting session with people from different countries and experiences. Together with some friends I have developed a route-setter way to grade the boulder or a route instead of the basic grade that is useless in competition. We noticed that it was possible for the best climbers to fall on a Font 7a (V6) and also to flash a Font 8a+ (V12) as they depend on many factors. We came up with a new idea of the RIC scale that is in fact three different dimensions: Risk, complexity and intensity. Playing with these three dimensions, mixing a bit like a DJ, it was possible to speak about it with an understandable language without discussing the grade for long. Now should this way of doing it be a basic standard of route setting? Even if it's not formal, it always somewhere in our mind.

Given all the experience you have gained throughout your climbing career, what advice would you give to climbers, at any level?

Everyone is unique but if I have to share some words that suited my style I would say: Curiosity, joy, the training it needs and no limits for the brain.

Editor