Focus: Graham Dunning Interview

Photo: Julien Kerduff

Focus explores creative talent within the climbing community.

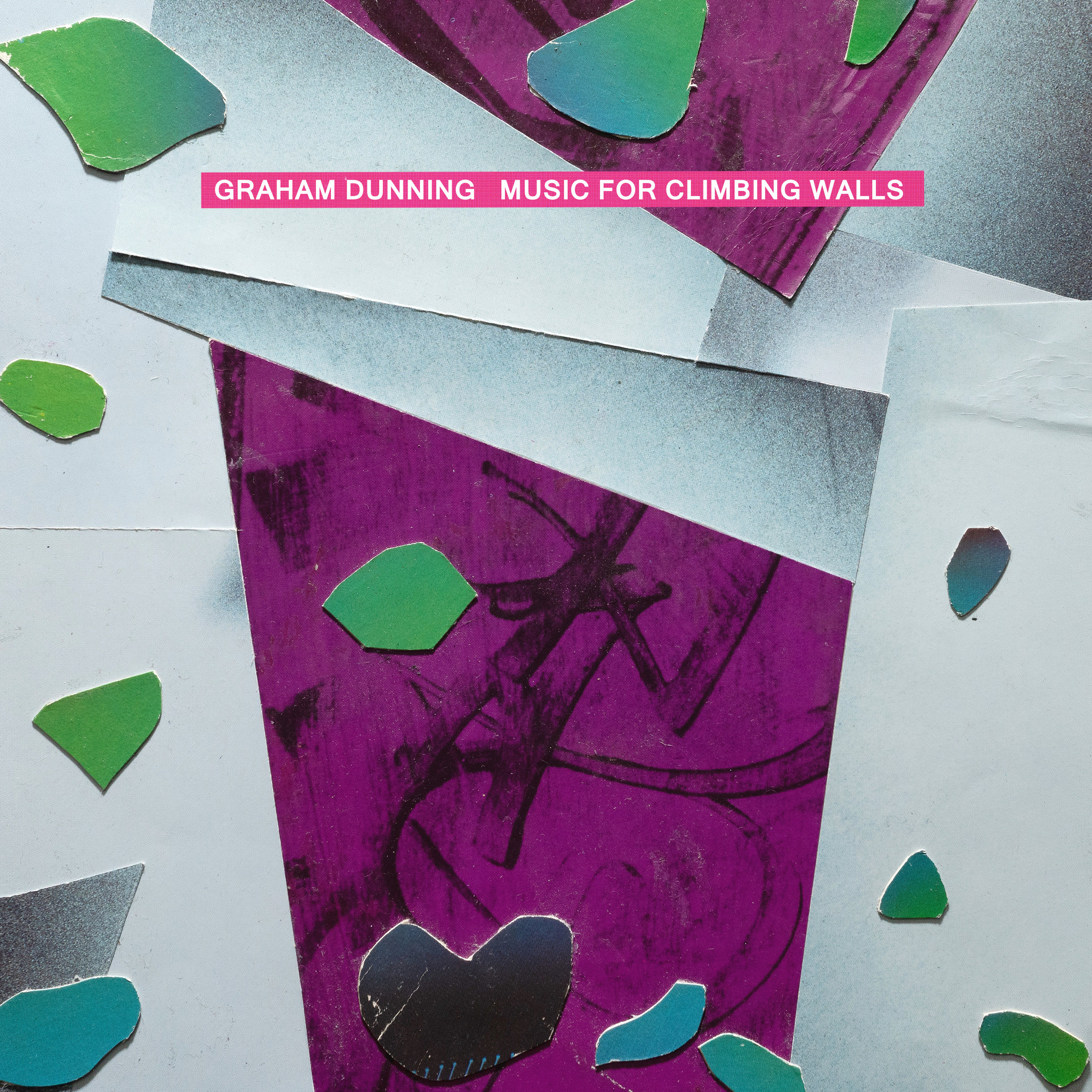

London-based musician and climber Graham Dunning takes an unusual approach to music production. While most electronic music exists almost entirely within the confines of abstract numerical structure, Dunning’s approach involves running modified vinyl records from a spindle extension at the centre of a turntable. He calls this method mechanical techno, the results are imperfect and often accidental but also uniquely physical. He has just released a new album on LTR Records called Music For Climbing Walls.

Music For Climbing Walls… a nod to Brian Eno’s Music For Airports?

Yes, kind of a tongue in cheek thing, but I’m also referencing the functionality of dance music.

How would you describe what you do?

It’s is a way of making rhythmical electronic music using modified records stacked up on a tower, a rotating sequencer triggering sounds from different sources. I started off by playing noisy, abstract shows with several turntables, scratched up and retextured records and guitar effect pedals. The mechanical techno machine is deliberately wonky, allowed to wobble a bit… not made too perfect. In developing this method I recognised early on that this was important to its sound, I made a conscious effort not to iron out the creases. Over time I began to focus more on rhythm and started introducing synths and electronic drum sounds. The project evolved through studio experiments and playing lots of live shows.

Does your music belong in any particular genre?

Many genres are firmly established but also generally fuzzy at the edges and, especially in electronic music, new sub-genres are constantly being born. I’m interested in music which is peripheral or doesn’t quite fit within a specific genre. Tracks which sound like they have something slightly off or amiss–pushing at the edges of a genre.

My favourite time frame for music is around 1991 when British dance music was evolving at a fast pace, ‘ardcore’ was still coagulating in to jungle and happy hardcore, there were all kinds of styles and sub-genres emerging. I like that kind of uncertainty in genre, it feels like anything can happen because the rules haven’t been set in stone yet.

What are your thoughts on the new album? Specifically how the music relates to climbing and your own music making process.

The album is called Music For Climbing Walls, not music for climbing. Although I actually think it is pretty good music to climb to. I’m interested in how the shapes and colours of indoor climbing walls create geometric, rhythmical and abstract sculptures with a functional and sometimes beautiful logic of their own. I started to see a connection with my music and its layers of clean and dirty textures; pointillist scree behind rubbery rhythms, overlapping and interlocking surfaces. This is reflected in the album artwork: collages made from record sleeves and illustrations of climbing walls.

The way I make music is physical. Both in the sense of building an actual machine and for my body too because I need muscle memory for adjusting parts of the system, like the position of the drum triggers. The recording sessions for the album took place over a wintry, rain-soaked week at a studio in Margate on the south coast. Towards the end I felt absolute cabin fever, stressed out, climbing up the walls. I feel like this mood comes through in the tracks.

You were taking photos at every wall you visited, some of which ended up being used to make the record cover.

Yes, the album artwork is basically collages made from record sleeves and illustrations of actual climbing walls. Again showing multiple layers of texture. It’s the walls themselves that particularly interest me. Designed as a kind of riddle – the routes are also referred to as problems – when you know how the logic works you can start to decode them. But it’s not possible to just look at the problem and work out the solution visually: your body needs to test the options, feel the holds, try out the stretches and the pulls.

To me climbing seems to exist outside the confines of what is usually considered sport… how do you feel about it?

I’m not interested in the competitive side of climbing. Learning to climb is about learning to use your body in a different way, solving problems physically as well as mentally. Good climbing is about efficiency rather than strength or speed.

Tim Featherstone is a climber and journalist based in Cumbria, he also runs LTR Records