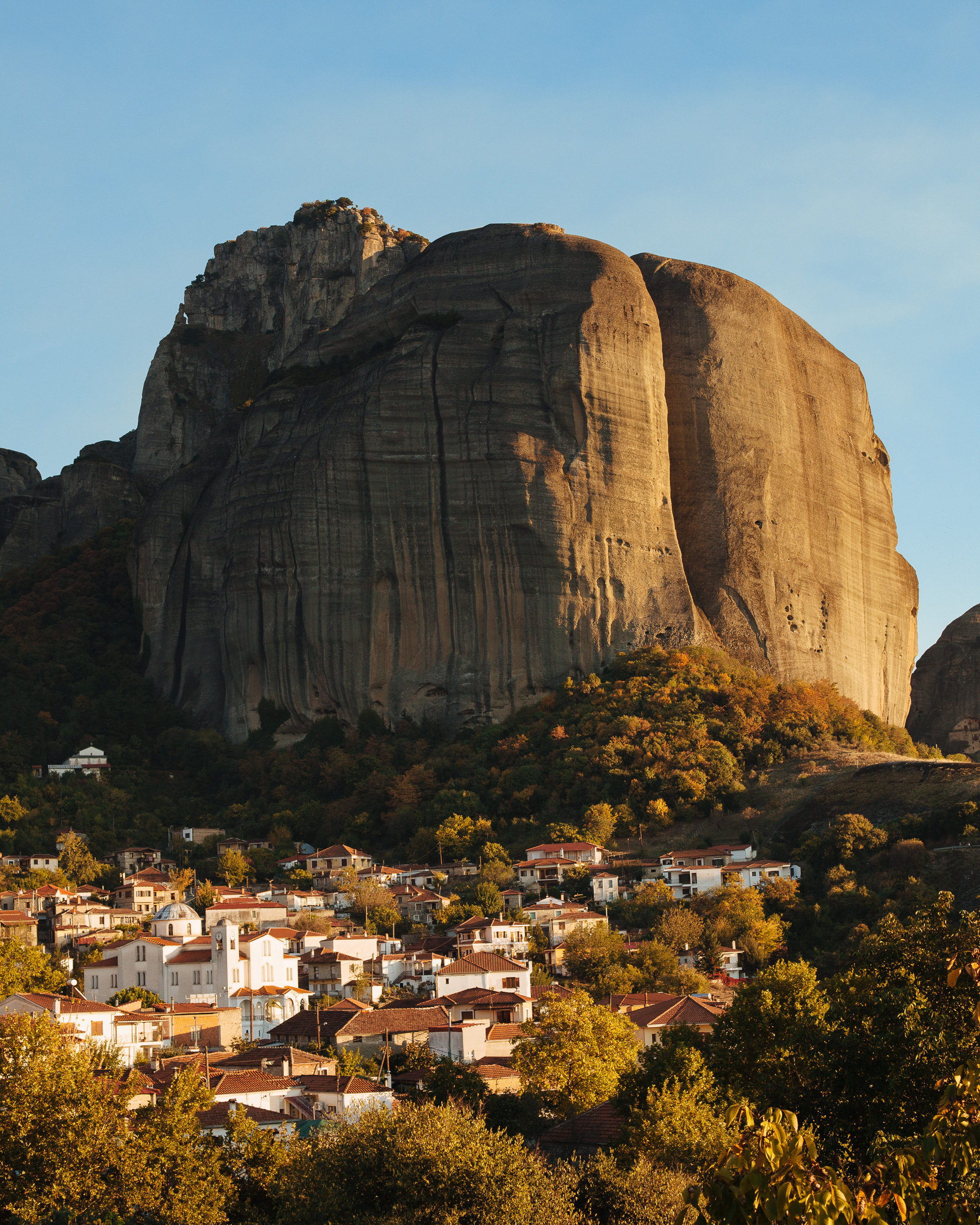

Suspended In Air

Stood in a chimney—chute or ‘way of the water’—my thoughts wander to how on earth I ended up here again? I should have known better, having visited the previous year, tempted by an Instagram post from the 2014 Petzl RocTrip. I’d managed to convince my partner for that previous trip, my dad, away from the relative comfort of Lake District trad climbing and the somewhat diminutive buttresses of Northumberland for a week of classics in Meteora—which itself means ‘suspended in air’. Although protection was somewhat sparse, the mega-classics on our agenda were well trafficked, and the week went without a hitch, barring one altercation with a ring bolt and a poorly placed knot when descending from Yspiltoera, the ‘highest place’.

The route below had lulled me into a false sense of security that this was a sport-route, rather than the bold fare that is so characteristic of Meteoran climbing and the Saxonian climbers who initially ascended these conglomerate towers (free soloing Monks aside). Famously, in 1975, a 14th century summit cross—taller than a man, or certainly me—was removed for refurbishment by helicopter and now resides within the Varlaam monastery; the rock itself shows no signs of having been climbed by artificial means. No chipped holes for siting ladders, unlike the majority of the other surrounding formations, which leaves you wondering quite how they managed the ascent.

However, with a jolt I am brought back to my current predicament. My chosen footholds alarmingly, and simultaneously, break away from the rock. The face which was littered with alternate choices sized anywhere from a marble to a cannon ball, all somewhat dubiously attached compared to the perfect pitches of steep black rock that preceded this indignant—and on paper, simple—exit onto the top of the Holy Ghost (or 'Heiliger Geist'). There’s little choice remaining, other than admitting defeat and slinking back towards the belay and ultimately the floor, but to tentatively move upwards strictly maintaining three points of contact whilst remembering the stark warnings described in the guidebook by Stasse and Hutte (1986, 2000).

'It cannot be emphasized enough that anybody wanting to climb the Meteora rock towers, the majority of which are very difficult to tackle, will need a great deal of mountaineering experience and sound rock-climbing equipment. Any attempts to climb the rocks without these essential pre-requisites are, as a rule, irresponsible and could even be fatal.'

Clipping the mid 45m pitch bolt—the sole fixed protection beyond the previous bolt, almost clip-able from the belay itself—offers brief mental respite before continuing climbing in search of the next belay, leaving only one more pitch before the summit and a chance to sign the register. The climbing whilst never physically demanding consists of bridging, palming and generally doing anything possible to avoid pulling. The free-hanging rope below disappearing out of sight providing a constant reminder that the position was neither comfortable or safe. Atop each tower, a summit register is kept within a small metal box, secured to the rock with a pole and u-shaped channel. In each, one can find a few pencils, a sharpener (if lucky) and a register to simply sign your name, the date, and the style of ascent of your chosen route. Some registers date back to the original ascent of the towers.

From the summit of the Holy Ghost one can truly appreciate a unique view of Meteora—itself a UNESCO world heritage site—with some of the active monasteries (Roussanou, Varlaam, St. Nicholas Anapavsa and Great Meteoron) precariously perched atop the surrounding cliffs amongst numerous abandoned monasteries and hermitages alike.

This is my second time on the summit, the first just a day before via the outrageous Pillar of Dreams ('Traumpfeiler), which somehow weaves its way up the highest point of the buttress, past the last wooden remains of an abandoned prison, at an incredibly accessible grade of 6a (5.9). Although, with 2-3 bolts per pitch, and with some pitches approaching 50m, one can be excused for climbing well within yourself.

There are no crowds on the summit to disturb you, instead tourists gather en-masse to watch the sunset from the opposite side of the valley, rapidly dispersing soon after. It’s unlikely even that your peace will be broken by another climbing party on all but the most popular routes. Suddenly I remember 'how on earth I’m back here' and resolve to be back here before too long.

Climber, and reluctant engineer based in Lancashire